by Andrés Cisneros-Montemayor

The United Nations Oceans Conference, held this June (2017) at the UN Headquarters in New York City, aimed to be “the game changer that will reverse the decline in the health of our ocean for people, planet and prosperity.” Though it might seem lofty, this stated intent is actually relatively modest; reversing current trends is literally the first step towards achieving the sustainable and equitable use of our ocean resources, especially if we truly want to achieve much broader human sustainable development. I participated in the Conference and associated meetings together with other members of the Nippon Foundation Nereus Program, where we are working and collaborating with others to emphasize and integrate climate change and social equity considerations into science-based environmental and development policies.

General Assembly during the UN Oceans Conference, UN Headquarters, NY.

The author and a fellow N-Gener, María José Espinosa Romero, at the UN Oceans Conference.

The Oceans Conference is part of an encouraging trend towards intergovernmental sustainability and environmental policies. This meeting was officially named the “High-level United Nations Conference to Support the Implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 14: Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development.” The UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a set of 17 goals—each with specific targets—ranging from ending world hunger and poverty, achieving peaceful societies, protecting our marine and terrestrial ecosystems, and mitigating anthropogenic climate change (see figure below). The UN Oceans Conference focused on Goal 14, ‘Life Below Water’, but a key theme throughout presentations, declarations, negotiations, and hallway discussions was the importance of linking ocean issues with global sustainable development. This has been a key component of my and many others’ research, including a new study, ‘A rapid assessment of co-benefits and trade-offs among Sustainable Development Goals’, that brought together experts from many different fields.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

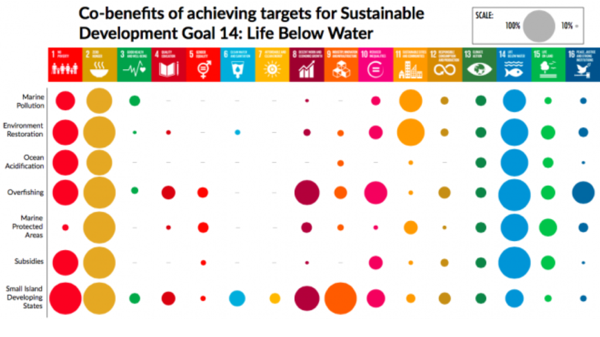

This research, led by fellow Nereus Program member Dr. Gerald Singh, evaluates how achieving the ‘Life Below Water’ targets contributes to and in many ways is required for achieving the other SDG targets. For example, results showed that curtailing overfishing and ensuring equitable distribution of benefits (specifically highlighted through Small Island Developing States and Least Developed Countries) are expected to have the most positive impacts on other SDG targets (see figure below).

Co-benefits of achieving SDG 14: Life Below Water targets for other Sustainable Development Goals. Size of the bubbles denotes the proportion of targets within each goal (top) that co-benefit from achieving each ocean target (left). From Nippon Foundation Nereus Program, 2017.

From a policy perspective, this framework allows one to better address a common question implicitly—or sometimes openly—posed by policy-makers regarding ecological conservation or social equity: “Why should I care?”

Pollution, habitat restoration, acidification, overfishing, protected areas, subsidies, and equitable benefits for the least developed nations are addressed within marine and coastal contexts of SDG14. By accomplishing this oceans-centered SDG, however, one would make significant headway into alleviating poverty, ending hunger, providing decent work, increasing gender equality, and promoting peaceful societies. The oceans are only one example of the complex social-ecological systems in which we live, and the framework itself is designed to be applied to any similar theme.

To help bring these scientific findings into the policy arena, a summary report was launched during a Side Event (an official presentation within the conference programming) titled ‘The Role of the Oceans in Sustainability: Benefits of Achieving SDG 14 for all Sustainable Development Goals.” Discussion at this event brought attention to needed integrated, interdisciplinary and cross-sectoral partnerships to achieve the SDGs. Perhaps the most important take-home message from these efforts is that social equity and climate change issues are inextricably tied to the health and sustainability of our oceans, and to the rest of our social-ecological systems.

The official outcome of the Conference, “Our Ocean, Our Future: Call for Action,” states an agreement by nations “to act decisively and urgently, convinced that our collective action will make a meaningful difference to our people, to our planet and to our prosperity.” It includes clear language regarding the need to consider and incorporate the impacts of climate change and human industries on the marine environment, and to involve indigenous peoples, women and a wide array of stakeholders in policy development and implementation.

A close reading of the document reveals the many ambiguities and policy gaps inherent to such an agreement, but I can only be hopeful that it is a start to meaningful actions on the part of governments responsible for the management of their own resources. In the Gulf of California and Sonora Desert region, we recognize perhaps more than ever that the flagship conservation challenges of our lifetimes are not solely ecological, but are deeply rooted in social and political issues; such is the case with fisheries and bycatch in the Upper Gulf of California, or the severing of ecosystems by existing and proposed border walls.

In addition to their concrete targets, the UN Sustainable Development Goals provide a guide to force us to broaden our perspective of what is at stake in efforts for the conservation of biodiversity and sustainable management of natural resources. Intra-linking the UN Sustainable Development Goals makes clear that working together and reaching far across our disciplines and contexts is the only way we can collectively succeed.

Dr. Andrés Cisneros-Montemayor is the Program Manager for the Nippon Foundation Nereus Program, and a Research Associate at the University of British Columbia. He specializes in resource economics and sustainable development strategies.