Scott Bennett, Michael Bogan, Michael Darin

“You know, at one of these freshwater springs I’ve been studying, there are these striations on the rocks and the steep-walled canyon comes to an abrupt end, as if the Earth is opening up, “ aquatic ecologist, Michael Bogan told geologists Scott Bennett and Michael Darin. “We could all hike there the day after tomorrow”.

The multidisciplinary hook was set.

Immediately following the October 2015 Summit of the NGEN Sonoran Desert Researchers, Bogan, Darin, and Bennett were set to explore Cañón La Navaja and its tropical freshwater oasis –– Darin and Bennett for the very first time; Bogan through a new lens. The three scientists woke early, used satellite imagery to scout the landscape and the approach, and commenced on a 3 km hike into the Sierra El Aguaje. The destination was a tropical palm oasis that Bogan has been conducting repeat surveys since 2004 to document the biodiversity of these well-hidden groundwater-fed aquatic habitats.

Leading the traverse, Bogan spoke of the spectacular freshwater oasis and aquatic taxa (Pic 1) the group should expect at the canyon terminus. Bennett and Darin, in typical geologist form, lagged behind, distracted by the tilted Miocene-age volcanic rocks –– lava flows that erupted from a chain of volcanoes ~15 million years ago (Pic 2). They made observations about faults, where cliffs of these thick lava flows appeared to be truncated and juxtaposed against a dissimilar rock type (Pic 3). Bennett and Darin, having conducted over a decade of combined geologic and tectonic research in Sonora, hypothesized that these faults are likely related to the rifting and faulting that formed the Gulf of California basin. They noticed one location where the fault was contouring along the side of a mountain, directly through a cluster of large palm trees (Pic 4). After they drew the fault line on their map, Bogan pointed out that the largest known desert rock fig tree (Ficus petiolaris palmeri; 35 m-diameter canopy) is located directly on the mapped fault (Pics 5 & 6).

Coincidence?

Earlier that week, all three had participated in a half-day excursion with dozens of other NGEN Summit attendees to the nearby Nacapule canyon, another research locale of Bogan. In Nacapule, Bogan led the group in a discussion about the extraordinary diversity and endemism of aquatic species in the canyon’s pools and trickling water. Richard Felger pointed out the botanical diversity of the canyon, particularly the various tropical species that somehow thrive in this desert outpost, including figs, palms, and flowering shrubs. Other tangential conversations developed organically, with topics varying from butterflies and freshwater invertebrates (Pic 7) to land management practices, tourism, and water resource conservation. But Bennett and Darin were hot on the trail of something different, something that moves much slower than butterflies or water. They noticed that the Nacapule tributary canyons not only hosted the groundwater-fed springs that sustained the canyons flora, but also that these tributaries had eroded their steep canyon walls along another geologic fault.

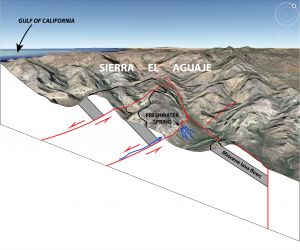

A pattern was emerging: fault lines in the Sierra El Aguaje –– where rocks grind past each other –– commonly correspond with groundwater-fed springs.

This concept is not new to geologists. Groundwater can flow more easily along fault zones, where the rock mass is broken and more permeable. Millions of years of crushing and grinding during hundreds to thousands of earthquakes causes rocks adjacent to fault zones to exhibit a greater amount, and more connected network, of fractures. This fracture network, if not cemented and blocked by precipitation of mineral-rich fluids, can serve as a conduit for the migration of fresh water in the subsurface. If the correct hydrologic conditions are present, this groundwater can make it to the surface, forming freshwater springs (Pic 3).

Back in Cañón La Navaja, Darin, Bennett, and Bogan reached the canyon terminus and were rewarded with the cool trickle of fresh water flowing down the 40 m-high cliffs of volcanic rocks that surrounded them on three sides (Pic 8). They examined the freshwater pools (Pic 9) for leopard frogs (Pic 10) and aquatic insects and searched the fractured cliffs for evidence of faulting. Bogan noticed various dragonflies (Pic 12) and water bugs, just a few of the more than 130 aquatic taxa known from La Navaja. Darin and Bennett measured near-horizontal striations on polished fault surfaces, caused by grinding of rocks during paleo-earthquakes, and clear evidence for strike-slip faulting (Pic 12). They collected as much data as they could about how the rocks have moved along these faults, but it would take much more time to fully document and characterize the geologic history, and for Bogan the modern biodiversity, of this vast sierra.

On the hike back down through the Cañón La Navaja (Pic 13), the three field scientists pondered their observations, their new multidisciplinary connections, and shared their excitement to return to the Sonoran Desert to further study the Sierra El Aguaje. An important lesson they learned through this experience was that it is difficult, if not impossible, to observe everything at once in the Sonoran Desert, or in any landscape for that matter. The only patterns we are able to notice are those that are familiar to us. Working with scientists across different disciplines and sharing observations can allow new and important patterns to emerge (Pic 14), allowing our collective scientific endeavors and knowledge to push forward into new directions.